This article was written for Run4Your Life Magazine

Many individuals who enjoy participating in running sports are high achievers who balance numerous responsibilities every day. Work, study, relationships, training and competition, we aim to do it all and we aim to do them all well. Balancing daily responsibilities with our desire to fulfill athletic ambitions is a fine balance. Modern lifestyles can be stressful. It is easy to get caught off-guard by an unexpected stressor and precariously close to feeling fatigued and overreached. The purpose of this article is to explain the stress response that occurs in these situations and to identify whether chronic or long-term stress increases our risk of injury.

Stress: The flight-or-fight response

Stress is defined as the body's reaction to a change in our normal, steady state that requires a physical, mental or emotional adjustment or response. Stress can also be defined as a condition of the mind-body interaction and the sum total of all mental and physical inputs over a given period of time [1, 2]. There are many different forms of stress that athletes are placed under. Short-term stressors such as hard training sessions, competitions or busy workloads are normal and our body’s adjust to these responses relatively easily. However, many athletes chronically overload their bodies with heavy or high-volume training and continual complex lifestyles. Controlling our response to acute or chronic stress is the brain. It differentiates between the different types of stressors, determines the behavioural and physiological responses, and determines whether the response will be health-promoting or health-damaging [2]. The stress response is often referred to as the flight-or-fight response.

Walter Bradford Cannon first described the flight-or-fight response in the early 1900s. His theory hypothesized that an animal reacts to threats with an activation of the nervous system that primes the animal for fighting or fleeing [3]. Today, the flight-or-fight response is fundamental to explaining our bodies’ reaction to a stressor. This includes, but is not limited to: an acceleration of the heart and lungs; the relocation of blood to the heart, lungs and muscles of movement; inhibition of the gastrointestinal tract; and mobilization of energy sources [4].

The stress response and development of Allostatic Load

The flight-or-fight response causes our brain to undergo changes in order to direct our body systems into either an action or shutdown mode. Directly affected are the metabolic, cardiovascular, immune and skeletal systems via neural and endocrine inputs. The brain’s neural and hormonal activities initially protect us and lead to allostatis or a stabile state of adaptation. However, over time the allostatic load can accumulate and an overexposure to neural, endocrine and immune stress mediators can have adverse effects on our organ systems [2, 5]. This can set a life-long pattern of behavior and physiological reactivity. There are two important body systems that participate in maintaining allostasis during stressful situations, the endocrine and nervous systems [2].

.png)

The endocrine response: Stress hormones

Physical and emotional pressures both provoke a response by the two adrenal glands situated near the kidneys. The adrenal glands produce two primary hormones, cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) [1]. Both cortisol and DHEA are considered the major ‘shock absorber’ hormones in the body and the marker most commonly used to measure acute and chronic stress levels is the blood concentration of cortisol.

Cortisol

Cortisol is a steroid hormone involved in the regulation of essential bodily functions [6]. Cortisol secretion increases in response to any stress in the body, whether physical or psychological.

It acts to regulate blood pressure, cardiovascular function, and the body's use of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats. When cortisol is secreted, it causes a breakdown of muscle protein, leading to the release of amino acids into the bloodstream for use by the liver to synthesize glucose. Cortisol also leads to the production of energy from fat cells to use by the muscles in times of ‘starvation’, such as when running a marathon. Together, these energy releasing processes prepare the individual to respond to the stressors.

The body possesses an elaborate feedback system for controlling cortisol secretion (which is beyond the scope of this article). However, prolonged exposure to stress can alter the accuracy of this negative feedback loop resulting in excessive levels of cortisol acting in the body.

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)

DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone) is the most abundant hormone found in the body’s bloodstream. DHEA is vital to health [1]. In a normal steady state, the body produces large amounts of the hormone to: regulate hormonal actions by its role as a precursor to other hormones, such as estradiol and testosterone; increase fat metabolism to regulate energy and body temperature; generate the feeling of satiety; enhance immune protection; improve calcium absorption into the bones; act as an anti-inflammatory; and decrease the stress response [7]. When the body becomes chronically stressed, the adrenal glands decrease the production of DHEA. As Melamed [1] states, ‘DHEA is a good stress barometer, because when stress levels go up, DHEA levels go down. This then leads to a drop in other hormones, such as testosterone.’

Stress Hormones and long-term stress

When males and females participate in infrequent strenuous activity, such as running, the concentrations of both cortisol and DHEA increase until the demands on the body are met. For athletes who are constantly under lifestyle, training and competition pressures, cortisol levels can remain chronically elevated whilst their DHEA levels can become significantly depressed. These altered levels are a result of the adrenal glands that have shrunken and decreased their hormone production in response to the body’s chronic stress load [1]. The symptoms associated with adrenal dysfunction are diverse and can involve the digestive, circulatory, respiratory, as well as the brain and nervous systems. In addition, the adrenals can impact the growth and repair of bones, muscles, hair and nails.

Nervous System responses to stress

The nervous system is a network of interconnected nerves throughout the brain, spinal cord and peripheral neural pathways that act in response to external and internal stimuli via chemical signals. There are two types of neural input from the brain, the automatic and somatic nervous systems. Whilst the brain consciously controls the somatic nervous system, it subconsciously controls the automatic nervous system. For example, our routine breathing pattern is set by the autonomic nervous system but if we choose to, we can alter our breathing rate consciously through activation of the somatic nervous system.

Stress stimulates the autonomic nervous system and creates many physiological changes through activation of the sympathetic nervous system. It assists the mobility of blood to important parts of the body and also signals the adrenal glands to secrete adrenalin and noradrenalin, hormones that boost muscular energy and facilitate immediate physical responses in preparation for muscular exertion [8]. The nervous system is also involved in our ability to return to a relaxed state after exposure to a stressor. If a stressor is continually affecting our body, the nervous system remains persistently switched on in a flight-or-fight response and an alerted state all the time. This translates into a situation where the body cannot actually rest at all.

The chronic stress response in athletes

Athletes who are continually under voluntary and involuntary stressors are at high risk of causing long-term changes to their bodies. High training, work and social loads with inadequate physical and mental rest can lead to a chronically activated sympathetic nervous system and depressed adrenal glands. An over-stimulated nervous system will cause: alterations to sleep-awakening patterns; gut irritability and suppressed appetite; weight loss; agitation with poor concentration; and restlessness. This will lead to inadequate recovery from training and competitions with an increasing feeling of being ‘stressed out’. Simultaneously, hormone regulation patterns in the body will become disrupted resulting in increased cortisol and decreased DHEA levels. Cortisol has long been the marker for monitoring stress [9]. When exposure to stress is sustained, cortisol levels remain elevated and a build up of the hormone can be seen in the bloodstream and hair strands. More recently, blood DHEA levels have also become a marker of stress levels. Increased cortisol levels in athletes will: prevent the storage of glycogen in the liver and muscles; increase the breakdown of remaining body glycogen stores through glycogenolysis; increase the rate of protein breakdown leading the muscle wasting; affect the circadian rhythm sleep cycles; increase urination rates causing dehydration; and decrease bone formation. Decreased DHEA in athletes will result in: rapid breakdown of protein stores; an impaired ability to deposit calcium in the bones; a loss of adipose or fat tissue around the vital organs; suppression of the immune system; and generalized fatigue.

Therefore, when the body is continually trying to respond to chronic stressors, the athlete is at an elevated risk of muscle wasting, bone degradation, weight loss, disrupted sleep and immune suppression. It is well documented that a body in this state will inadequately repair existing injuries. However, little is understood about how this corresponds to elevated injury risks.

Chronic stress and the incidence of injuries

The link between stress and pain is well described in the scientific literature. For example, a study conducted by Melamed [1] showed that musculoskeletal pain is unusually high in the working population and in situations where there is no obvious cause of this pain, there is often a direct link to feelings of being chronically ‘stressed out’. The study conducted on otherwise healthy, non-athletic individuals concluded that chronic exposure to stress may lead to burnout. They concluded that burnout and stress appear to be a risk factor for unexplainable musculoskeletal pain.

It becomes more difficult to identify causes of pain and injuries in athletes who have many concurrent risk factors through continual demands on their bodies and minds. There are many researchers who have tried to identify and quantify the links between stress and sports injuries [9-11]. Most of the research that has been conducted into the relationship between stress and sports injuries has looked at how stress slows the healing response and not whether it can actually cause injuries.

Some of the research that has been conducted in this field of study has occurred within Australia. Researchers at the Queensland Academy of Sport recently completed a study in the psychological predictors of injury. Looking at health screenings of over 800 athletes ranging from 11 to 41 years of age, their results illustrated the huge scale of sports injuries prevalent amongst Australian athletes with no apparent cause. Through their research they found substantial links to athletes’ suppressed mood or elevated psychological tension and their injury and illness characteristics.

Another study conducted in 2003 looked at endurance athletes and the physiological changes that occur when they are exposed to prolonged physical stress over several months of the competition period [12]. They too concluded that elevated cortisol levels detected in the hair and bloodstream pointed towards an increased risk of the development and progression of both somatic and mental illnesses.

Implications for coaches and athletes

Cumulative pressures and a high allostatic load is inevitable in most high level sports. It is reasonable to assume that the capacity to respond appropriately to acute, superimposed physical and psychological stressors that add to the training and competition load will be limited in athletes. With research pointing towards a link between stress and injuries, monitoring athletes’ levels of physical and psychological expenditure would appear to be critical. As psychological stressor effects are mediated through the same pathways as physical stressors, athletes subjected to recent stressful life events have a higher cumulative allostatic load and an even more diminished threshold for mounting situational-appropriate ‘emergency’ responses. School, employment, transportation, social and emotional pressures must be taken into account when planning out training blocks. Further to this, the problem that many coaches and athletes face is that the boundaries between normal daily tensions, acute stress and chronic stress are difficult to distinguish.

The normal physical stress response in athletes

Acute physical exercise, a potent physical stressor, activates the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands and in turn, the normal stress response. When adequate recovery is allowed to follow bouts of physical activity, the athlete’s hormonal levels, including their cortisol levels, should return to normal. This would mean that the athlete returns to feeling calm with clear thoughts, normal appetite, insignificant muscle soreness and an ordinary sleep pattern. An athlete in this situation should be able to cope with a slow, aggregated and periodised training program.

When the normal stress response becomes abnormal in athletes

Prolonged aerobic exercise and endurance training induces the stress response pathway to release abundant cortisol an there is a linear relationship between training volume and cortisol levels [13, 14]. Therefore, as an athlete’s training mileage and intensity increases, cortisol levels can increase indicating an amplified stress response. This puts the athlete at greater risk of injury and a constant state of arousal. The athlete’s ability to recover from training would begin to diminish and performance would be affected. Evidence indicates that in severe circumstances, increased cortisol levels may predispose distance athletes to a number of diseases including immune suppression, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, depression, acute myocardial infarction and upper respiratory tract infections [6, 14].

Indicators of a disruption to the normal stress response in athletes would be: disturbed sleep patterns; continual musculoskeletal aches or pains; a loss of appetite and gastrointestinal troubles; weight loss and muscle dystrophy; restlessness and irritability; decreased bone density measures; and an inability to concentrate on mental tasks. This combination of factors is often described as athlete burnout.

Avoiding athlete burnout

Often overlooked, rest is a critical component to any training program. There are two forms of rest, active and complete cessation of physical activity. Gentle forms of exercise such as easy jogging or cross-training can be a great way for athletes to unwind whilst still completing mileage. However, without adequate sleep, nutrition and time away from the running shoes, athletes will put themselves at risk of chronically overreaching.

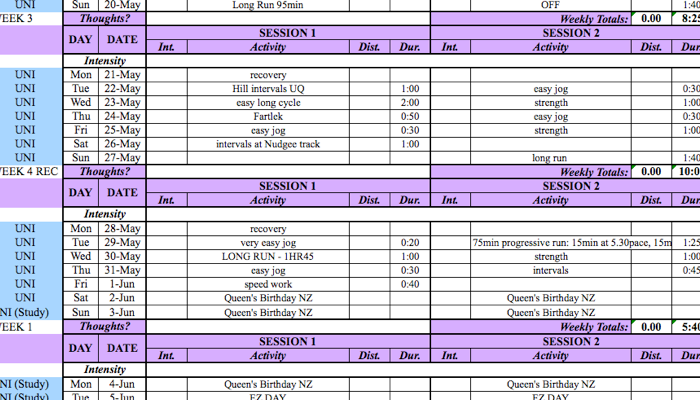

The most at-risk athletes are those that are self-coached. As a self-coached athlete, it becomes hard to look in from the outside at yourself and your training, and to see when the normal has shifted towards abnormal. It becomes difficult to distinguish between natural fatigue and feelings of stress, and those that are atypical. A coach can be the person to assist you to avoid overloading by keeping your sport and life in perspective. Nevertheless, at some stage all athletes will find themselves in an overreaching phase of training or intense competition. During these times, athletes are particularly vulnerable to allostatic loading and burnout. Ideally, when athletes are faced with times of increased mental demands, such as university exams, the training load will be decreased to compensate. As coach Max Cherry used to say, ‘when we are in a state if physical rest, the conscious and subconscious activities of the brain use 90% of the body’s energy’. Whether scientifically true or not, the concept is relevant. For elite athletes, the potential to eliminate physical stressors is limited so a potential avenue for decreasing allostatic load is to control or eliminate unnecessary psychological stressors [9, 10].

There are many psychological interventions utilized in sport. Notably, sports psychology has taken on an important role in preventing injury, illness and burnout. Psychologists introduce athletes to techniques such as breathing control, muscular relaxation, imagery, self-talk and cognitive reprograming. Using training planners to indicate when high-intensity activities are going to occur, such as competitions and examinations, will help to stave off chronically elevated stress levels. Further to this, integrating psychology and other remedial disciplines such as massage, chiropractics and physiotherapy into the training program can also help athletes to ensure that rest is actively incorporated into their weekly routines.

Away from the training arena, there are many services offered to assist in alleviating stress. Many universities, schools and workplaces provide links to councellors or life coaches to help individuals find an adequate balance between responsibilities and play. Vitamin D deficiency is now strongly linked to stress and illness, so finding time in the middle of the day for a walk, jog or lunch in the sunshine could be beneficial. Studies have shown that commuter behavior can also be a huge stress-producer so finding alternative options such as cycling or walking to your required destination could help to prevent stressful situations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the nature of sport and its association with high achievers places participants at increased risk of injury and illness. In runners, stress is a huge risk factor for athletic injuries due to its disruption to the normal hormonal and nervous system responses that normally have a preventative action during training and competitions. Athletes with a high allostatic load, caused by increasing physical and psychological pressures with no associated rest, are at the highest risk of causing chronic, physical changes to the body and its systems. Monitoring the stress load and compensating with moderations to the training program will help athletes to stay healthy and injury free.

References:

1.Melamed, S., Burnout and risk of regional musculoskeletal pain—a prospective study of apparently healthy employed adults. Stress and Health, 2009. 25(4): p. 313-321.

2.McEwen, B.S., Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: central role of the brain. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 2006. 8(4): p. 367.

3.Cannon, W.B., The mechanism of emotional disturbance of bodily functions. New England Journal of Medicine, 1928. 198(17): p. 877-884.

4.McCarty, R., Fight-or-flight response. Encyclopedia of stress, 2000. 2: p. 143-145.

5.Korte, S.M., et al., The Darwinian concept of stress: benefits of allostasis and costs of allostatic load and the trade-offs in health and disease. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2005. 29(1): p. 3-38.

6.Skoluda, N., et al., Elevated hair cortisol concentrations in endurance athletes. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2011.

7.Tanska, K. Muscle DHEA: The Mother Hormone. Muscle News 2012 [cited 2012 6 August ]; Available from: http://www.australianmuscle.com.au/muscle_news/dhea.htm.

8.Thompson, R.S., P.V. Strong, and M. Fleshner, Physiological Consequences of Repeated Exposures to Conditioned Fear. Behavioral Sciences, 2012. 2(2): p. 57-78.

9.Galambos, S.A., P.C. Terry, and G.M. Moyle. Incidence of injury, psychological correlates, and injury prevention strategies for elite sport. 2006. Australian Psychological Society.

10.Galambos, S., et al., Psychological predictors of injury among elite athletes. British journal of sports medicine, 2005. 39(6): p. 351-354.

11.Moyle, G.M. and P.C. Terry, Psychological predictors of injury in elite athletes. 2005.

12.McEwen, B.S., Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. European journal of pharmacology, 2008. 583(2-3): p. 174-185.

13.Schwarz, L. and W. Kindermann, β-Endorphin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol and catecholamines during aerobic and anaerobic exercise. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology, 1990. 61(3): p. 165-171.

14.Gow, R., et al., An assessment of cortisol analysis in hair and its clinical applications. Forensic science international, 2010. 196(1-3): p. 32-37.